Beverages similar to beer are produced in Japan (sake, from rice) and Mexico (pulque, from agave). In much of Africa, malted sorghum, millet, and maize (corn) are used to produce local beers such as bouza, burukutu, pito, and tshwala. The Tarahumara of Mexico incorporate the drinking of a maize beer, tesquino, into important social rituals.

In Europe the properties of the water used for brewing, the types of malt, the brewing practices, and the yeast strains have contributed to traditional distinctions between beers. Early British beers were made from successive extracts of a single batch of brown malt in a top-fermentation process. The first and strongest extract gave the best-quality beer, called strong beer, and a third extract yielded the poorest-quality beer, called small beer. In the 18th century London brewers departed from this practice and produced porter. Made from a mixture of malt extracts, porter was a strong, dark-coloured, highly hopped beer consumed by the market porters in London. Brewers in Burton upon Trent, using the famous hard waters of that region and pale malts roasted in coke-fired kilns, created pale ales, also called best bitter. Pale ale is less strong, less bitter, paler in colour, and clearer than porter. Mild ales—weaker, darker, and sweeter than bitter—are a common variation; more colour is obtained by special malts, roasted barley, or caramels, less hops are used, and cane sugar is added to impart sweetness and aid maturation. Stouts are stronger versions of mild ale; some, such as milk stouts, contain lactose (milk sugar) as a sweetener. Beers with alcohol content well in excess of 5 percent are produced in the United Kingdom (barley wines), Belgium, and the Netherlands (for example, Trappist beers).

Bottom-fermented lagers have their origins in continental Europe. Brewers in Plzeň (now in the Czech Republic) used local soft waters to produce the famous Pilsner beer, which became the standard for highly hopped, pale-coloured, dry lagers. Dortmunder is a pale lager of Germany, and Munich has become associated with dark, strong, slightly sweet beers with less hop character. The dark colour comes from highly roasted malt, and other characteristic flavours arise during the decoction mashing process. Bock is an even stronger, heavier Munich-type beer that is brewed in winter for consumption in the spring. Märzbier (“March beer”) is a lighter brew produced in the spring. While all German lagers are made with malted barley, a special brew called weiss beer (Weissbier; “white beer”) is made from malted wheat. In other countries such as Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United States, other cereals are used in lighter-coloured lager beers.

Lambic and gueuze beers are produced mainly in Belgium. The wort is made from malted barley, unmalted wheat, and aged hops. The fermentation process is allowed to proceed from the microflora present in the raw materials (a “spontaneous” fermentation). Different bacteria (especially lactic acid bacteria) and yeasts ferment the wort, which is high in lactic acid content. Lambic beer is the cask product sold locally. Gueuze is bottled and refermented lambic beer. Filtered gueuze, the most popular product, is a bottled blend of lambic and gueuze. A cask product made in a similar manner is thought to have been consumed by miners in the United States during the California Gold Rush.

The strength of beer may be measured by the percentage by volume of ethyl alcohol. Strong beers are in excess of 4 percent, the so-called barley wines 8 to 10 percent. Diet beers or light beers are fully fermented, low-carbohydrate beers in which enzymes are used to convert normally unfermentable (and high-calorie) carbohydrates to fermentable form. In low-alcohol beers (0.5 to 2.0 percent alcohol) and “alcohol-free” beers (less than 0.1 percent alcohol), alcohol is removed after fermentation by low-temperature vacuum evaporation or by membrane filtration. Other low-alcohol products may be produced from worts of low fermentability, using yeasts that cannot ferment maltose, or by mixing yeast separated from a normal fermentation with weak wort at a low temperature for a short time.

The 20th century saw the erosion of traditional distinctions based on place of manufacture, raw materials, and brewing methods. This has caused a reaction among a small body of consumers. In Britain it has encouraged support for smaller, traditional ale breweries. In the United States a growing number of “microbreweries” brew beers with more flavour and colour.

The brewing process

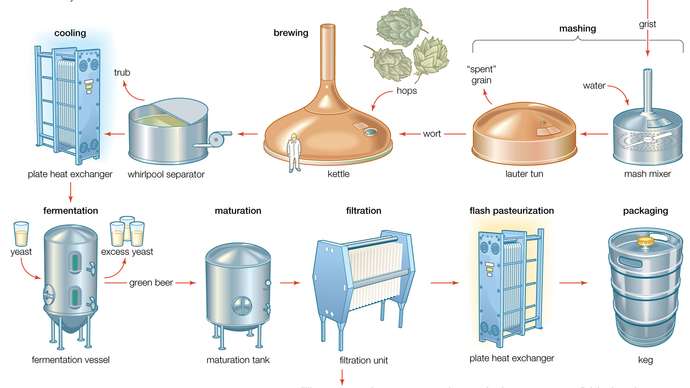

Beer production involves malting, milling, mashing, extract separation, hop addition and boiling, removal of hops and precipitates, cooling and aeration, fermentation, separation of yeast from young beer, aging, maturing, and packaging. The object of the entire process is to convert grain starches to sugar, extract the sugar with water, and then ferment it with yeast to produce the alcoholic, lightly carbonated beverage.

Malting modifies barley to green malt, which can then be preserved by drying. The process involves steeping and aerating the barley, allowing it to germinate, and drying and curing the malt.

In order to be fermented by yeast, the food reserve of barley, starch, must be converted by enzymes into simple sugars. Two enzymes, α- and β-amylases, carry out the conversion. The latter is present in barley, but the former is made only during germination of the grain. Specially bred strains of barley (generally low in nitrogen content) are used for malting. Other important characteristics are yield, even germination, ability to produce enzymes, and a highly extractable malt.

Steeping

Malting begins by immersing barley, harvested at less than 12 percent moisture, in water at 12 to 15 °C (55 to 60 °F) for 40 to 50 hours. During this steeping period, the barley may be drained and given air rests, or the steep may be forcibly aerated. As the grain imbibes water, its volume increases by about 25 percent, and its moisture content reaches about 45 percent. A white root sheath, called a chit, breaks through the husk, and the chitted barley is then removed from the steep for germination.

Germination

Activated by water and oxygen, the root embryo of the barleycorn secretes a plant hormone called gibberellic acid, which initiates the synthesis of α-amylase. The α- and β-amylases then convert the starch molecules of the corn into sugars that the embryo can use as food. Other enzymes, such as the proteases and β-glucanases, attack the cell walls around the starch grains, converting insoluble proteins and complex sugars (called glucans) into soluble amino acids and glucose. These enzymatic reactions are called modification. The more germination proceeds, the greater the modification. Overmodification leads to malting loss, in which rootlet growth and plant respiration reduce the weight of the grain.

In traditional malting, the steeped barley was placed in heaps called couches and, after 24 hours, spread on a floor to permit germination. Because respiration of the grain causes oxygen to be taken up and carbon dioxide and heat to be produced, control of aeration, ventilation, and temperature was achieved by manually turning the grain. Large-scale floor maltings with mechanical turners were introduced, later replaced by pneumatic maltings, in which germination occurred in boxes with the bed automatically turned, aerated, and ventilated with forced air. In some malting operations, gibberellic acid is sprayed onto the barley to speed germination, and bromates are used to suppress rootlet growth and malting loss. Although less-modified malts are traditionally used in lagers and well-modified malts in ales, it is now usual to produce well-modified malts regardless of whether lager or ale is to be made.Malting modifies barley to green malt, which can then be preserved by drying. The process involves steeping and aerating the barley, allowing it to germinate, and drying and curing the malt.

In order to be fermented by yeast, the food reserve of barley, starch, must be converted by enzymes into simple sugars. Two enzymes, α- and β-amylases, carry out the conversion. The latter is present in barley, but the former is made only during germination of the grain. Specially bred strains of barley (generally low in nitrogen content) are used for malting. Other important characteristics are yield, even germination, ability to produce enzymes, and a highly extractable malt.